350 Asia

BATAAN, Philippines

The Silent War of Bataan

As a 600-kilowatt coal-fired power plant threatens the community’s health and livelihood,residents call for a health study to explain the onslaught of skin and respiratory diseases in their town.

This story is part of the Storytelling Projects, Connecting The Dots, which try to follow fossil fuels finance in Asia.

Read More

During World War II, soldiers from Bataan province joined the main resistance of the Americans in the war against the Japanese.

But the long period of battle eventually left Filipino fighters defenseless, as they suffered from hunger, wounds, disease, and death.

Today, the people of a coastal town in Limay, Bataan province believe that the enemy is no longer foreign invaders, but a 600-kilowatt coal-fired power plant built on their land.

They remain at war with the daily whiff of white smoke from the plant’s chimneys and the ominous sound of its engines that spell the “slow death”—as they describe it—of residents who live just a few meters away from the colossal structure.

Surrendering is not an option for this community of 18,000, whose members have been fighting for their land and life since 2013.

Cherry Magracia, 50, of Lamao village in Limay town, said it was then largely unknown that a global power plant would be built in their community.

She said they were not consulted about the plan.

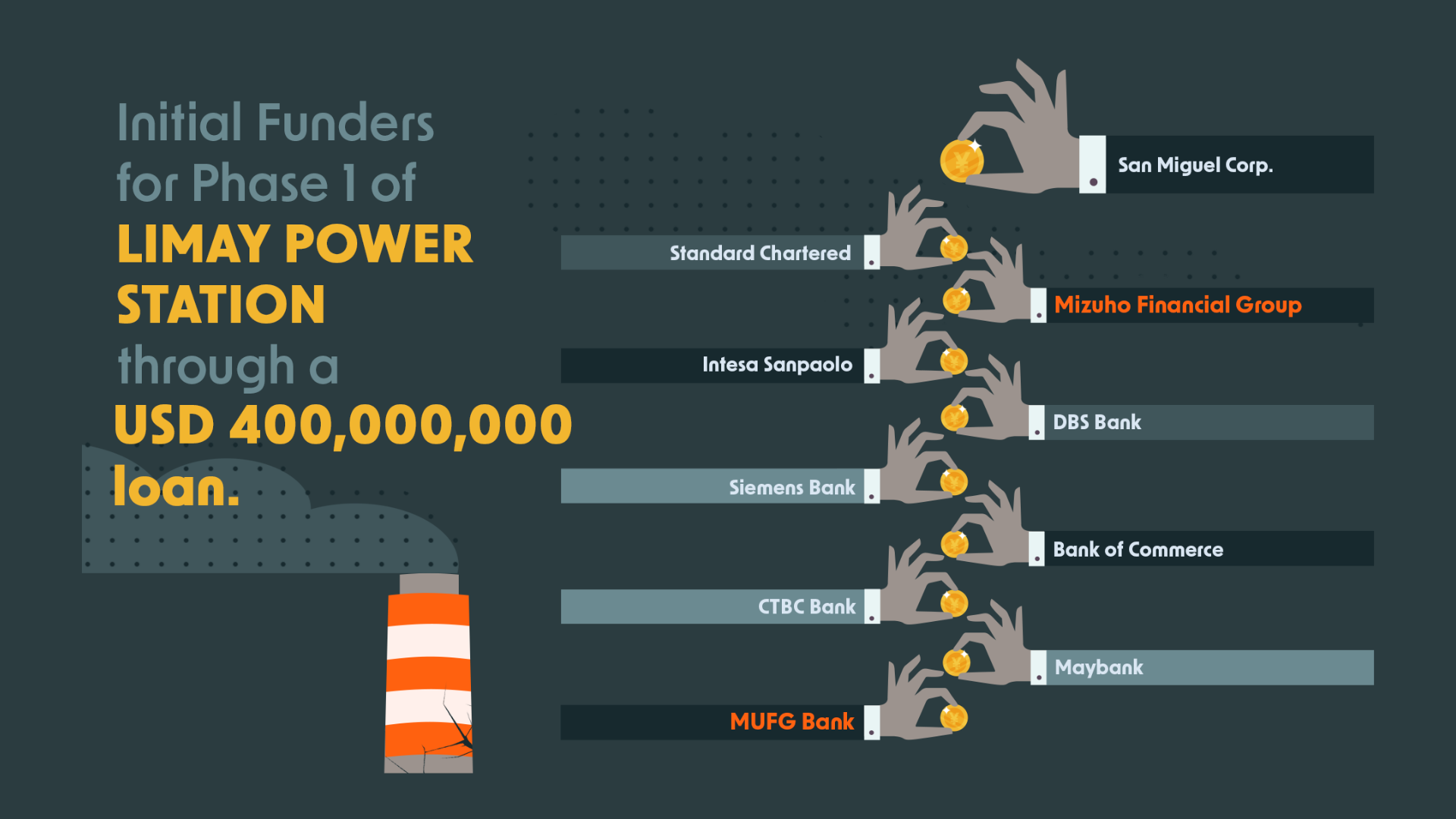

The project came to be known as the Limay Power Station of San Miguel Corporation Consolidated Power Corp — (SMCCPC), a subsidiary of multinational conglomerate San Miguel Corporation (SMC).

Now connected to the national power grid, the coal plant started its commercial operations in May 2017.

“Why are you doing this to us?” I asked the police. “Are we criminals?” Carina Dellosa, 50, recalled asking.

Told to Leave

Magracia said it was only through secondary channels that they knew about the proponents’ real intentions. They were being told to leave.

Magracia said the company offered to buy out the rights to their land for P25,000 to P300,000 (USD 460 to 5500), depending on the size of their houses.

“The compensation did not even cover the old trees that would be destroyed,” she said.

The provincial governor’s office was supposed to shoulder three months of rent at a temporary relocation area for families who would accept the offer.

“But it was unclear where the relocation site would be. And after those three months, how would we pay for the rent?” she asked.

While around 140 families were forced to relocate, Magracia and her family chose to stay.

Together with other members of the Limay Concerned Citizens Inc., an organization founded by the community, Magracia joined a series of protests resisting the construction of the power plant.

Other community women who rallied then said they were often blocked by armed security personnel and policemen.

“Why are you doing this to us?” I asked the police. “Are we criminals?” Carina Dellosa, 50, recalled asking.

Their resistance stemmed from the lack of proper relocation and their awareness of the power plant’s potential damage to the community.

“We wanted a relocation [site] where livelihood opportunities existed. And we want them to pay for the damages. That structure affected our health, our plants and our river. But all we got are empty promises, only verbal promises,” said Magracia.

“I’m not a smoker, but I feel like there’s always a lump in my throat,” said Dellosa, who also showed this journalist a red patch on her left foot that she said she acquired after the power plant was built.

Health impacts

Visitors in Lamao are greeted by a noxious smell—a faint stinging odor similar to burning plastic, rotten eggs or paint thinner. The unpleasant odor lingers in one’s nose, and gets stronger when the wind blows.

Dealing with this issue every day became a silent war for families who chose to stay.

Malodorous fumes from the power plant often cause discomfort and distress among residents.

Ever since the coal plant was built, many of them have developed skin, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases that never really went away.

The use of coal to generate energy was proven to have negative health conse-quences according to a 2013 study published by the University of Illinois at Chicago School of Public Health and international group Health Care Without Harm.

The study noted the “evidence of coal’s impact on human health during every stage of its use for electricity generation—from mining to post-combustion disposal.”

“Air pollution from coal plants affects respiratory and cardiovascular systems,

causes abnormal neurological development in children, poor growth of the fetus before birth, and cancer,” it added.

Children, the elderly, pregnant women, and people with lung conditions like asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are “especially vulnerable to health effects” of this kind of pollution, the study noted.

“I’m not a smoker, but I feel like there’s always a lump in my throat,” said Dellosa, who also showed this journalist a red patch on her left foot that she said she acquired after the power plant was built.

Dellosa found out a few years ago that her blood had high levels of arsenic.

“It’s getting harder for us to swallow, our mouths are dry, because of what we’ve been inhaling every day,” said Magracia, who has diabetes.

Access to comprehensive healthcare and appropriate medicines was also a huge concern in the community.

“If you’re poor and you’re feeling ill, you go to the health center. If you have money, you go to a private doctor. We have learned to live with that every day,” said Angeline Bolitres, 35.

Mothers complained that their children were frequently getting sick, while many pregnant women have died or lost their babies due to complications, according to the residents’ narration.

Results of a health complaints survey conducted from January 16 to 20, 2017 in Limay, as shared by the Coal-Free Bataan Movement, showed that 649 cases of various diseases were experienced by residents since the power plants were built in their town.

Cough and colds, skin rashes, headaches, asthma and primary complex were the top health complaints reported by the community.

Threats to Livelihoods

Even local fisherfolk were not spared. In 2016, the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources found out that fish samples from Limay had high levels of chromium, cadmium and mercury.

Long-time fisherfolk Fred Dela Cruz said that fishes in their area were often driven away by “bad water,” which he believed was seawater mixed with the power plant’s chemical waste.

“The area where the coal plant now stands used to be part of our fishing grounds. Now, they’re prohibiting us from entering a huge part of the sea because, as the guards tell us, the company has already bought the area,” said Dela Cruz.

“But I told them, isn’t the sea supposed to belong to fisherfolk too, not just private companies?” he said.

Alvin Pura, who used to work in power plants in other provinces, said the ash emitted by the facilities would stick to their clothes, make their skin itch and eventually lead to other ailments.

His daughter developed asthma at a young age. This is why he, too, decided to stand up against SMC’s coal-fired plant.

Sign Up

Connecting the Dots

Get the full hi-resolution copy of the Connecting the Dots e-book by signing up. We will update you with information about this and upcoming projects, and opportunities to take action. Be part of our growing movement in Asia.

Sign up to learn more and receive updates about this project.

Legal Battle

In January 2017, the regional office of the Environmental Management Bureau (EMB) ordered SMCCPC “to stop any activity inside its coal-fired power plant in Limay, Bataan in the wake of an ash spill” the previous month.

The incident “has reportedly caused several residents to fall ill,” according to EMB.

The SMCCPC deployed doctors to aid ailing residents in Lamao but touted to the press the “low emissions levels” of its “clean coal” power plant in Bataan.

Following the ash spill incident, it was business as usual for the power company.

The people of Limay, however, “were forced to adjust to the power plant, instead of the power plant adjusting to the people,” said Pura.

“If you complain, they will tell you: There’s nothing we could do, it’s already been built,” Pura said.

Limay residents are asserting the need for an epidemiological study in Lamao, in order to gather new evidence of the power plant’s health impacts five years after it started running.